The Geography of Japan KEY Facts and Figures For You To Know

A country’s geography can have an infinite number of significant effects and influences upon its culture and society. The location of the country can change how it has intercultural influences with its neighbours or lack thereof. The size of a nation can and the actual land cover can drastically affect demography, development of social structures, and its position on the world stage. The topography of a country can dictate how a large percentage of its people earn their living, and finally, a countries climate can influence agriculture and the style of living.

While not crucial for living life in Japan, knowing about the country’s general geography and how it has affected its development and society over the course of millennia’s can be vital in understanding more about the complexities of the country and why it is as of today.

Location and Size

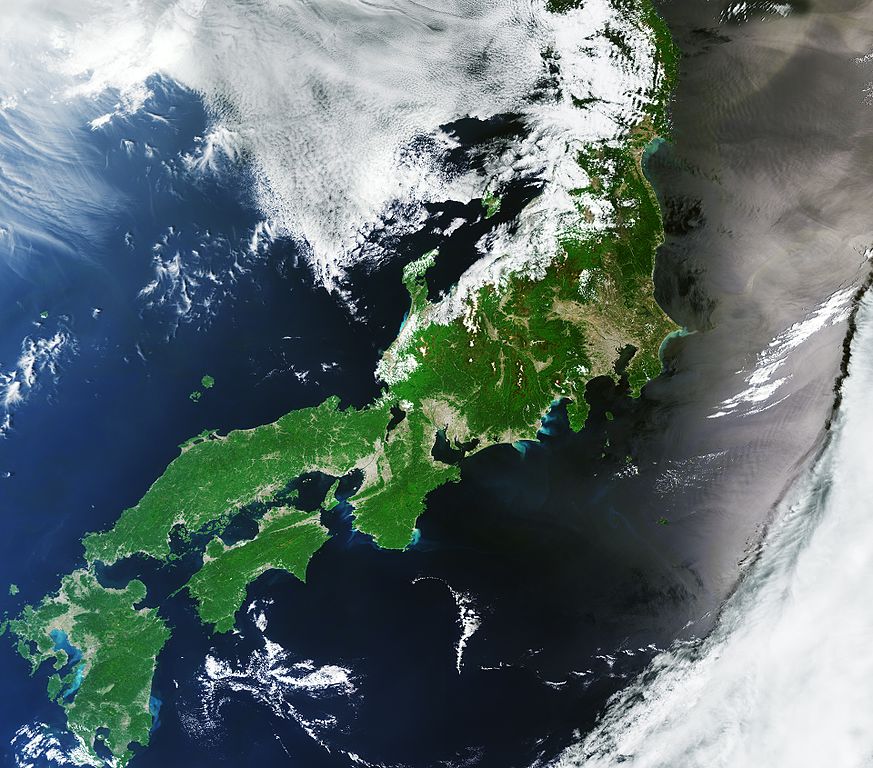

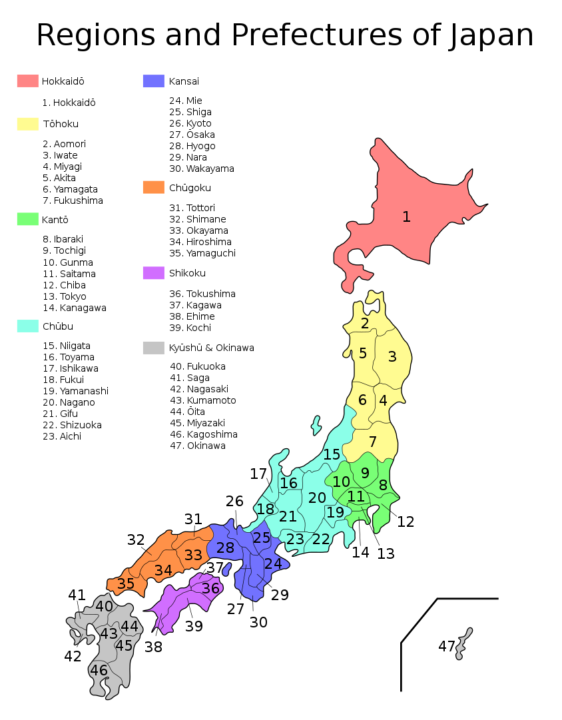

Japan is a shimaguni (island country), the Pacific Ocean to the east, the Sea of Japan to the west, and the East China Sea to the south. The Japanese islands are a stratovolcanic archipelago comprised of four main islands called Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, and Hokkaido and 6,852 smaller surrounding islands 145,936.52 square miles of land. Making it slightly larger than the United Kingdom, slightly smaller than California and approximately the same size as Germany, and one twenty-fifth the size of the United States. Japan is then divided into 47 different state-like prefectures.

The nearest countries are Korea, Russia, and China. The closest part of the mainland is Korea, 120 miles due northwest of Kyushu. To put this into perspective, the English Channel separating England and France is only 21 miles wide.

Japan’s situation as a shimaguni that is so especially far off the coast compared to other island nations of a similar size, such as England, has helped in their historically isolationist and xenophobic attitudes. An example of this is Sakoku, “Closed Country,” a self-imposed period of isolation that lasted from 1639 to 1853 that closed Japan off from most of the world. However, due to this isolation, Japan’s culture and customs are so pure and unique to their way of life today.

Japan’s islands make up less than 15% of its total territory, nearly all of which is located in the seas. In addition to the 200 nautical miles of the ocean than Japan claims around the main islands, according to the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, it can also claim 200 nautical miles around far-flung Japanese islands that extend from near Taiwan and China to far out in the Pacific Ocean.

Topography

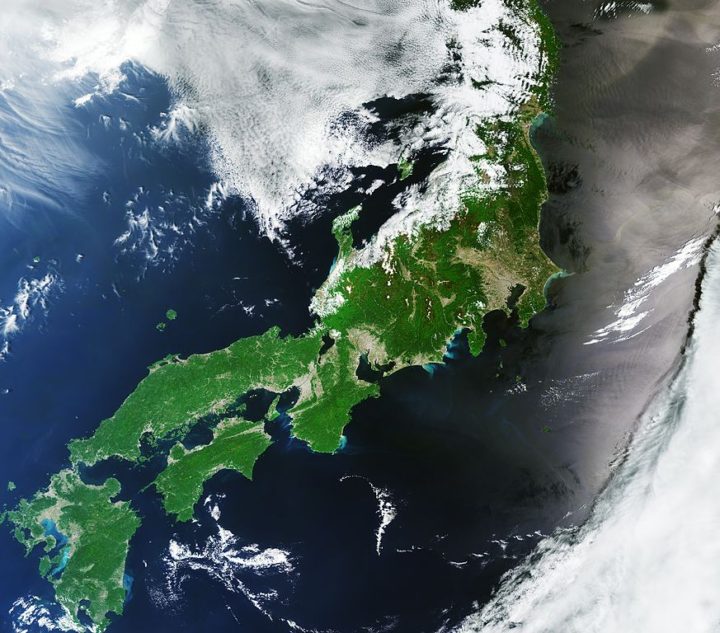

Around 73% of Japan’s terrain is mountainous, with large mountain ranges running through each of the main islands. The mountain with the highest elevation is the famous Mount Fuji, with a height of 3,776 m.

Japan’s forest cover rate is 68.55% since all the mountains within the nation are heavily forested. Finland and Sweden are the only other developed nations with a similarly high forest cover percentage.

Relatively little of Japan’s landmass is suitable for agriculture, at only 12.8%, which is also the only land suitable for living. Meaning the areas of population and agriculture are very interconnected within Japan. When comparing Japan to mainland Asian countries such as China, where they have masses of open space and land, it can be easy to see why the Japanese have developed in the way they have. Clustered, community-based, and nature-loving try and conserve as much of the little hospitable land they have.

With small amounts of little level ground, many hills and mountainsides at lower elevations around towns and cities are often heavily cultivated to try and make up for the lack of flat agricultural land.

The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan measures Japan’s territory annually to grasp the national land continuously. As of January 2018, Japan’s territory is 145,936.53 sq mi. It increased in the area due to the volcanic eruption activity of Nishinoshima and the natural expansion of the island. According to the Japanese Government in 2002, their land area was only 145,900 sq mi.

Rivers, Lakes, and Coasts

Rivers are generally steep and swift, and few are suitable for navigation except in their lower reaches. While most rivers are less than 300 km in length, their rapid flow from the mountains provides a valuable, renewable resource: hydroelectric power generation. Japan’s hydroelectric power potential has already nearly been exploited to its limits. Seasonal variations in flow have led to extensive development of flood control measures.

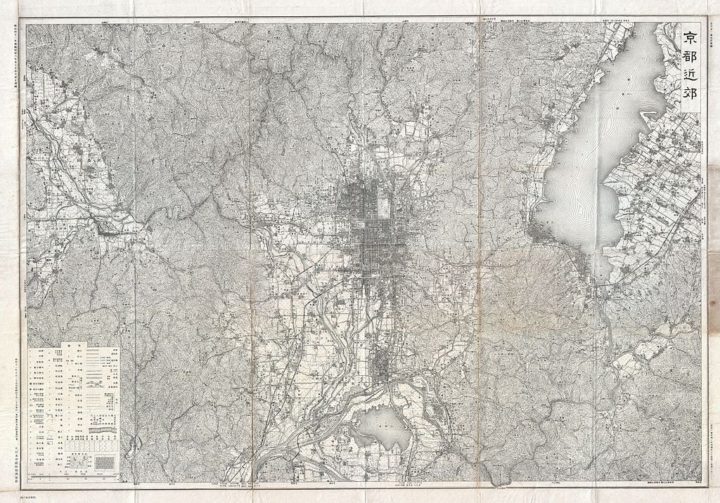

As stated, most rivers are relatively short compared to rivers in the rest of the world. The longest river, the Shinano, which winds through Nagano Prefecture to Niigata Prefecture and flows into the Sea of Japan, is still only 367 km long. The largest freshwater lake is Lake Biwa, at 671 km2, just northeast of Kyoto.

To compensate for the lack of navigable rivers within Japan, there is extensive coastal shipping around the Seto Inland Sea.

The pacific coastline south of Tokyo is characterised by long, narrow, gradually shallowing inlets produced by sedimentation, which has created many natural harbours. Simultaneously, the Pacific coastline north of Tokyo, the coast of Hokkaido, and the Sea of Japan are generally unindented, with few natural harbours.

Climate

Most of Japan’s regions, such as much of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, belong to the temperate zone, which has a humid subtropical climate characterized by four distinct seasons. However, its climate varies from the cool and humid continental climate in the north like Hokkaido to the warm and tropical rainforest climate in the south such as Ishigaki and Yaeyama.

Japan’s varied climate causes it to be split into six distinct geographical climate zone.

- Hokkaido, 北海道. Hokkaido has long, cold winters and cool summers, with not much precipitation in the humid continental climate.

- The Sea of Japan, 日本海. The northwest seasonal wind in winter gives heavy snowfall, where if it falls south of Tohoku, it will melt before the beginning of spring. During the summer, it is a little less rainy in the Pacific area, but there will sometimes be periods of extremely high temperatures due to the foehn wind phenomenon.

- Central Highland, 中央高地. A typical inland climate that gives large temperature variations between summers and winters and between days and nights. The precipitation is lower here than on the coast due to rain shadow from nearby mountain ranges.

- The Seto Inland Sea, 瀬戸内海. The mountains in the Chugoku and Shikoku regions block the seasonal winds and bring a mild climate with many fine days throughout the year.

- The Pacific Ocean, 太平洋. The climate varies greatly between the north and south, but generally, the winters are milder and sunnier than those on the side facing the Sea of Japan. Here summers are hot due to southeast seasonal wind, and precipitation is very heavy in the south and heavy in the north. The Ogasawara Island chain in the Pacific Ocean ranges from a humid subtropical climate to a tropical savanna climate with temperatures warm to hot all year round.

- The Ryukyu Islands, 南西諸島. The climates of these island chains range from the humid subtropical climate in the north to tropical rainforest climate in the south with warm winters and hot summers. Precipitation here is very high and is affected especially by the rainy seasons and typhoons.

Plains

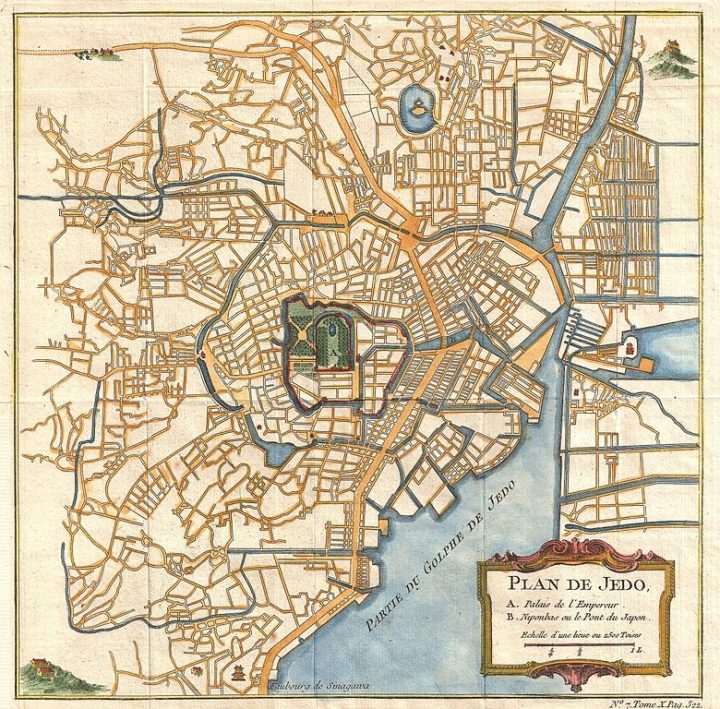

There are 3 major central plains in Japan’s biggest island of Honshu. The largest one being the Kanto Plain, which covers 6,600 sq mi, the capital of Tokyo, and the second-largest metropolitan population is located there. The next most extensive plain is the Nobi Plain, at 690 sq mi with the third most populous urban area Nagoya. The third-largest plain is the Osaka plain, which covers 620 sq mi in the Kinki region, and it features the second-largest urban area of Osaka. Osaka and Nagoya both extend inland from their bays until they reach their steep mountains.

The Kanto, Osaka, and Nobi Plains are the most important areas of Japan. They are economical, political, and cultural hotspots. These plains house the largest parts of Japan’s population, clustered into these coastal and fertile areas, meaning high agricultural production and large bays with ports for fishing and trade. The Kanto Plain became Japan’s seat of power, with that area now housing 42 million people, a third of Japan’s population. It grew here due to its intense agricultural production, meaning there was more food than could be taxed by the Tokugawa Shogunate in charge at the time of its growth.

Hokkaido also has multiple plain areas; numerous farms are situated within that grow a plethora of agricultural products. The average farm size in Hokkaido is 26 hectares per farmer, while the national average is 2.4; this helped Hokkaido become the most agriculturally rich prefecture of Japan. One-quarter of Japan’s arable land is located in Hokkaido, along with 22% of forests.

Geology

Geologically, Japan is one of the youngest inhabited areas on earth, still regularly experiencing volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. Around Tokyo, much of the landscape is made up of marine sediments deposited when the site was occupied by the seas – covered by multiple layers of ash from Hakone, Mt. Fuji and other volcanoes.

Japan lies on the Pacific Ring of Fire and is home to 108 of the world’s 1,500. Having more than 10% of the world’s active volcanoes, Japan has classified all their volcanoes on a scale of A to C, A having more volcanic activity. Some volcanoes have erupted 400 times a year. However, Mt. Fuji is classified as an active volcano even though it has not erupted since 1707.

Japan is riddled with faults and is located at the junction of four tectonic plates. The last 75 years have seen the Japanese archipelago and surrounding areas hit with five earthquakes that have measured more than eight on the Richter scale and 17 or more measuring measures above seven on the Richter scale. It is unlikely and unusual for there to be a year without four or more earthquakes that measure 6.0 or more.

Patchwork

American novelist Paul Theroux wrote that “Japan is almost without a hinterland. Its population lives mainly on its coast. The mountains are for tunnelling through, not residing on. And where there is open landscape, as in the low rolling hills of Hokkaido, it is thinly settled. From the carriage window, as the train travels north from Tokyo, through Sendai and the coastal towns of Minamisanriku, Kesennuma, Okuma, and others – the ones know away – the Japanese can be seen living in unusual urban density, the low, snug houses, traversed by narrow lanes, as they have been throughout history. I sense that they have been able to live closely together because of their elaborate good manners, mutual respect, self-sufficiency, and work ethic. A less polite society would require more space or higher fences or guard dogs.”

He then also writes “With this acute sense of limited land and few natural resources, and the hostility of nature, they have taken pains to put off the evil day by manipulating their weird geography, even if it means a disfigurement. The result makes the strange Japanese landscape even more peculiar: it is the most possessed-looking place imaginable, its awkward-seeming features ordered and buttressed, the human hand visible everywhere. The notion of control and containment, which dominates Japanese life, dominates the landscape Rivers are cemented into place, embarkments are tiers of concrete blocks; sidewalks and bridges exist in the most unlikely places. The 33-mile Seikan Tunnel that links Honshu to Hokkaido under the Tsugaru Strait is the world’s longest railway tunnel. The watchtowers and sea walls all over the coast reinforce the look of Japan as a fortress in the sea. It is, of course, an illusion.

In this quote, Paul Theroux summarises very nicely how Japan and its people have had to adapt to each other and develop alongside each other to survive a climate and location that is fiercer than it seems as first glance. With little ground to grow, harsh varied climate and the ever-looming chance of natural disaster the Japanese people have developed their culture and customs to suit the island that they have called home for 1000s of years

Ordered, efficient, respectful and above all, resourceful. These are qualities that the Japanese archipelago requires its residents to have to survive.